In August 1934, the St. Croix River reached its lowest level in more than 100 years of record keeping. A gauge in St. Croix Falls showed the river water flowing at just 6,000 gallons per second. That’s a trickle compared to its typical 30,000 gallons.

This nadir came at the end of a devastating stretch of dry years that plagued the Midwest and Great Plains starting in 1930, during the Dust Bowl era. Later analysis revealed 1934 was probably the worst drought in the region in 1,000 years. Sandbars and rocky river bottom must have emerged from the St. Croix, with what little water was left twisting between.

The St. Croix River was narrower and shallower 100 years ago than it is today. More rain, new precipitation patterns, deforestation, and other forces are widening and deepening it.

In April of 2001, the St. Croix hit its highest flows since people started tracking it, with 500,000 gallons of water per second rushing downriver at St. Croix Falls. Dikes were built to protect homes and businesses and all boating was prohibited as the river reached its second-highest crest in recorded history at Stillwater. (There is a strong connection between river flows in St. Croix Falls and water levels 25 miles downstream at the head of Lake St. Croix, but it’s not exact.)

The extremes of 1934 and 2001 are part of a much bigger story about how the St. Croix River has changed in the span of a few human generations — and why.

Growing flows

USGS Gage at St. Croix Falls

In 1902, the U.S. Geological Survey started measuring the flow at St. Croix Falls, Wis. The scientific agency has continued doing it to this day, currently operating a station on the Wisconsin side, situated between the Xcel Energy dam and the basalt gorge of Interstate Park. The instruments are housed in a small shed on the bank, recording measurements of flow, depth, temperature, and more every 15 minutes.

Reliable, consistent data is available from 1911 on, meaning anyone can explore 110 years of river flows and see what it says. The world has changed a lot in that time, and so has the St. Croix.

Looking at this significant span of time, it’s plain to see that more water flows down the St. Croix in this century compared to when measurements began at the start of the 20th century.

Between the first half of recorded measurements and the second period, average annual flow has increased by about 1,000 cubic feet (6,000 gallons) of water per second, from 3,900 to 4,900. That’s 23 percent more water.

The next question is where this extra water came from. There is more than one part to that answer.

Wetter weather

Another long-term measurement effort helps explain where the extra water in the St. Croix is coming from: Precipitation has increased significantly in the region of eastern Minnesota and northwestern Wisconsin that drains to the river.

The National Weather Service has rainfall and snow records going back to 1895, and the areas that drain to the St. Croix got an average of two more inches per year in that time.

The charts below show rainfall for Pine County — the largest county entirely in the watershed. The numbers across the region are very similar.

That’s not the whole story, though. Not only is more rain falling every year, how and when and where that rain is falling has also changed.

The increased frequency of freak storms — huge amounts of rain falling in a short time on a small area — have hit the St. Croix hard. “Extreme rain events” have wiped out dams, flooded cabins and homes, washed away soil and vegetation, and cut a wider channel for the St. Croix.

Floods are what usually carve a river channel, eroding banks and establishing high water marks.

The frequency of freak storms is not very obvious in annual statistics, as a small extreme rainfall might not change overall annual precipitation much. Historical records of extreme rain storms are also unreliable, as the events are so quick and localized that they’re easy to miss.

If nothing else, the data show that the biggest floods are getting bigger.

Peak flow — how much water ran past the river gage at the highest point each year — shows the highs are higher than ever.

Wider waterways

More rain and bigger storms add up to more water in the river. More water makes a bigger river, as the current eats away at the soft banks.

The lower St. Croix River is not simply a channel of water, but a broad floodplain with sandy islands, the river braided throughout. Every year, the water washes away different parts of the bank, cutting under trees at the edge, which eventually fall into the river.

It’s a natural process that can be amplified by changes in river flow. It also happens too slowly to see, but steadily. The river is always cutting new courses, with new land replacing the old, so detecting any long-term change is difficult.

Fortunately, we have many photos of the river, beginning around the same time that scientists started measuring precipitation and river flow. Photographs capture a single moment in time, and can be deceiving. There have been dry years during wet decades, and vice versa.

But a sample of historic photos shows a river that looks different than what is familiar in modern times.

In 1938, the state of Minnesota arranged for aerial photos to be taken of the entire state. Pilots flew grids taking high quality images. All those images are online thanks to the University of Minnesota’s Borchert Map Library. They are an invaluable tool for studying change over time.

The two image comparisons above were created using these 1938 aerial photos and modern imagery provided by the state of Minnesota. The changes are subtle, and the river conditions depend on the day the airplanes flew overhead, but a close looks shows how the water has risen and carved a broader channel.

More rain every year and bigger floods have caused the St. Croix to widen itself. These changes are closely connected to changes caused by humans — and can be fixed by people, too.

CO2 and H20

It’s not possible to link any one weather pattern or storm to climate change or any other cause, but more intense, concentrated rainstorms are part of the predictions for how global warming will affect the St. Croix River region. These forecasts are based in physics, chemistry, and other sciences, and have been largely accurate in short-term predictions so far.

Carbon dioxide and other gasses cause a greenhouse effect on Earth. By holding more of the sun’s heat, more water evaporates, and the air can hold more of it — until it lets loose with rain.

While the river flows have grown and the channels have widened, greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere have also increased by more than 40 percent. Average temperatures have also risen.

“An observed consequence of higher water vapor concentrations is the increased frequency of intense precipitation events, mainly over land areas,” NASA reports. “Furthermore, because of warmer temperatures, more precipitation is falling as rain rather than snow.”

The National Climate Assessment, which was released in 2014, concurred in its chapter on the Midwest. The report was based on extensive peer-reviewed research, and produced by a team of more than 300 experts guided by a 60-member advisory committee, and extensively reviewed by the public and experts.

“Extreme rainfall events and flooding have increased during the last century, and these trends are expected to continue, causing erosion, declining water quality, and negative impacts on transportation, agriculture, human health, and infrastructure,” the report says.

Fewer forests

Another part of the explanation may be deforestation of the river’s watershed. White pine were the first to go, but other lands were later cleared for farming or development. It’s much like what is happening in the Amazon now.

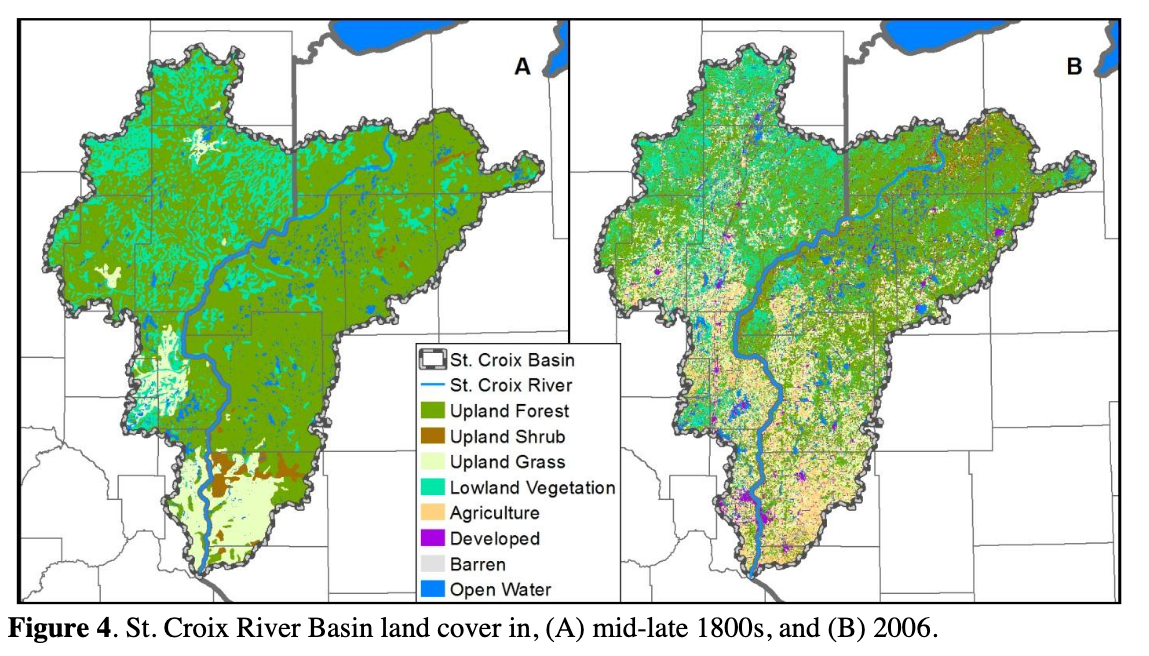

In fact, both the St. Croix and Amazon watersheds have lost about 20 percent of their forest in the last 160 years.

Before European settlement and widespread development and agriculture, the St. Croix’s watershed was about 66 percent forest — today it is about 40 percent.

Between the mid 1850s and today, the St. Croix basin lost more than one million acres of forest. It has been replaced by a half million acres of crop fields, a quarter million acres of developed lands, and other uses.

Deforestation has major effects on wildlife, destroying habitat for plants and animals, but it also threatens the St. Croix River — from its clean water to the welcoming beaches. Fewer trees on the banks, bluffs, and upland areas mean rainwater can flow much faster into the river.

Old growth forests soak up water through their roots and breathe it out their leaves or needles when photosynthesizing, returning it to the atmosphere. Fields and parking lots don’t. Tree roots hold soil in place, preventing erosion and gullies that only flush water faster toward the river.

Change is the only constant

The magic of rivers is that they are always changing. It’s a normal and necessary part of their nature. Moving water is a powerful force, and regularly reshapes channels.

But extensive data and scientific analysis shows that the St. Croix River’s recent changes are not entirely normal. The river is likely changing faster than ever, and more than ever. Humans are causing these changes, and are the only ones who can prevent future problems.

“All measures of conservation, as well as all technologies meant to wean us from fossil fuels, are worth pursuing in the same way that doing something is always more than doing nothing,” scientist and Minnesota native Hope Jahren says in her book “The Story of More: How We Got to Climate Change and Where to Go from Here.”

Numerous ways exist to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and slow down global warming. One effective way is planting more trees — which could not only capture more carbon but also help reforest the St. Croix’s watershed.

The river is still magical today, thanks to the foresight of people who loved it long ago. It’s up to stewards today to decide if it will remain a place of beauty, wildlife, and recreation for future generations.

Information sources

- Annual average flow: USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics for the Nation – St. Croix River at St. Croix Falls, WI

- Precipitation trends: NOAA National Centers for Environmental information, Climate at a Glance: County Time Series

- Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere: Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California

- Climate change impacts on precipitation: National Climate Assessment – Midwest; The Water Cycle and Climate Change – NASA Earth Observatory

- Deforestation and land cover: St. Croix River Basin – State of the Forest Report March 8, 2013 Jeff Reinhart, Minnesota Forest Resources Council

Comments

St. Croix 360 offers commenting to support productive discussion. We don’t allow name-calling, personal attacks, or misinformation. This discussion may be heavily moderated and we reserve the right to block nonconstructive comments. Please: Be kind, give others the benefit of the doubt, read the article closely, check your assumptions, and stay curious. Thank you!

“Opinion is really the lowest form of human knowledge. It requires no accountability, no understanding.” – Bill Bullard

9 responses to “Two inches and 6,000 gallons: A swollen century on the St. Croix River”

The water that is held back by the lock and dams in the Mississippi contribute to the higher water levels in the St. Croix.

Dams on the Mississippi might contribute to higher flood levels at Stillwater, but do not affect the amount of water flowing past St. Croix Falls, which this analysis focuses on.

Nit-picky Dept: 1cu ft = 7.48 gallons

I enjoy seeing data comparison charts over the past hundred years. The problem is obvious as is the solution. I just hope people can see from history about the effects people have on climate like the “dust bowl” years show on the charts. I still remember my grandparents talking about how they had to change their farming methods as did farmers across the county to resolve huge dust storms.

Minnesota Prairielands once protected moisture in the soils. Once the prairie grass was plowed under for wheat and corn that soil asperated into the atmosphere – which returns as ncreased precipitation. Arbor Day arrived in Minnesota in 1871 and Pioneers began planting trees everywhere.– increasing the aspiration of moisture into the atmosphere that returns as precipitation. White Pine forests have been replaced with all sorts of mature trees that are over a hundred years old now. There are more trees in Minnesota then at any time in history. Hybrid corn aspirates a gallon of water per stalk per day. Now GMO corn aspirates 2 gallons of water per day per stalk. Of course Minnesota and Wisconsin would become wetter now then anytime in history. The historic Mississippi River was wide shallow and slow flowing at 2 miles per hour. The deep water Channel system converted the Mississippi to a flow of 4 miles per hour doubling its rate. This also permits an increased flow of the St. Croix. As such, the Mississippi River Dam at Red Wing has had a nill affect. This article needs to be rewritten.

Ken – I’ll wait to see your data. You are absolutely right that prairie is extremely helpful for preventing runoff, but I didn’t have time to work that in, and I believe it’s better known than the effect of deforestation. Additionally, only the lower watershed was really prairie, and most of the drainage above St. Croix Falls (where the measurements were taken) was forested. While I appreciate your insights, the fact you say there are more trees in Minnesota than ever, while ignoring the very real fact that there is 20 percent less forest in the St. Croix watershed than pre-settlement, casts doubts on the rest of your assumptions. I don’t see how channelization on the Mississippi would somehow increase the amount of water flowing past St. Croix Falls either. Evapotranspiration is indeed an important and under-appreciated aspect of the water cycle, but you’re confusing some facts about atmospheric moisture. Prairie grasses aspirate a lot of moisture as well, operating most of the warm weather season, while corn is only growing for a couple months out of the year. I realize this post challenges some popular assumptions, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong. Greg

PS. Maybe these maps will help make sense of it:

Really interesting article. Walked south of the Dock Cafe and noticed old railroad ties suspended in the air- definitely a sign of the banks eroding.

The picture of the 1930’s vs now also shows the effect of of the “Wild River” legislation. All those farm fields would be subdivided now. The amount of trees regrown is noticeable.

Great article, Greg!!!